Female Self-Fashioning: Laura Knight & Greta Gerwig

Quarantine is perhaps the most appropriate time to catch up on Oscar films. Amongst the nominees, one buzzworthy film is Greta Gerwig's adaptation of the Louisa May Alcott novel Little Women. The film was deservingly selected for best costume designer, picture, actress, supporting actress, original music, and adapted screenplay. But, unfortunately, it was absent from one distinct category, best director-- a category of solely male nominees.

The Academy has only nominated five women in its longstanding history, of which Kathyrn Beglow has won. So, it is an unfortunate yet predictable reality that the 2020 Oscars featured a similar pool of all-male directors. Many found Gerwig snubbed, sharing disdain through memes and tweets. Regardless of the Academy's decision, Gerwig's undertaking is worth noting as it reorients the perception of women in film, women portrayed by women.

Little Women's plot is carried by the four March sisters, each with their distinct personas. Jo March, the passionate writer, is the most gender-bending of the bunch and prioritizes creative genius over romantic pursuits. Gerwig hones in on Jo, granting her character the most screen time. This creative choice is no surprise as Jo serves more than a fictional role, reflecting the personal life of the novel's author, Alcott.

Thankfully in this day and age, women in art is not an outlandish concept. However, this current norm was not the reality for the pioneers in the industry. Instead, art was cemented by the strict standards of institutions, such as the British Royal Academy of Arts. The high entry barriers of this institution, and others alike, made it near impossible for women to gain entrance.

Women's exclusion in the art world stemmed from many factors. Scholar Linda Nochline hypothesizes in her piece, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists," that one prominent obstacle was the lack of education. Art education often took the form of life classes, which prohibited women. Life classes were vital as an artist's depiction of a female nude solidified their status. Thus, for many years, women remained outsiders to the industry. Until 1936, the British Royal Academy finally granted artist Laura Knight full membership as its first woman member, despite its 1768 founding.

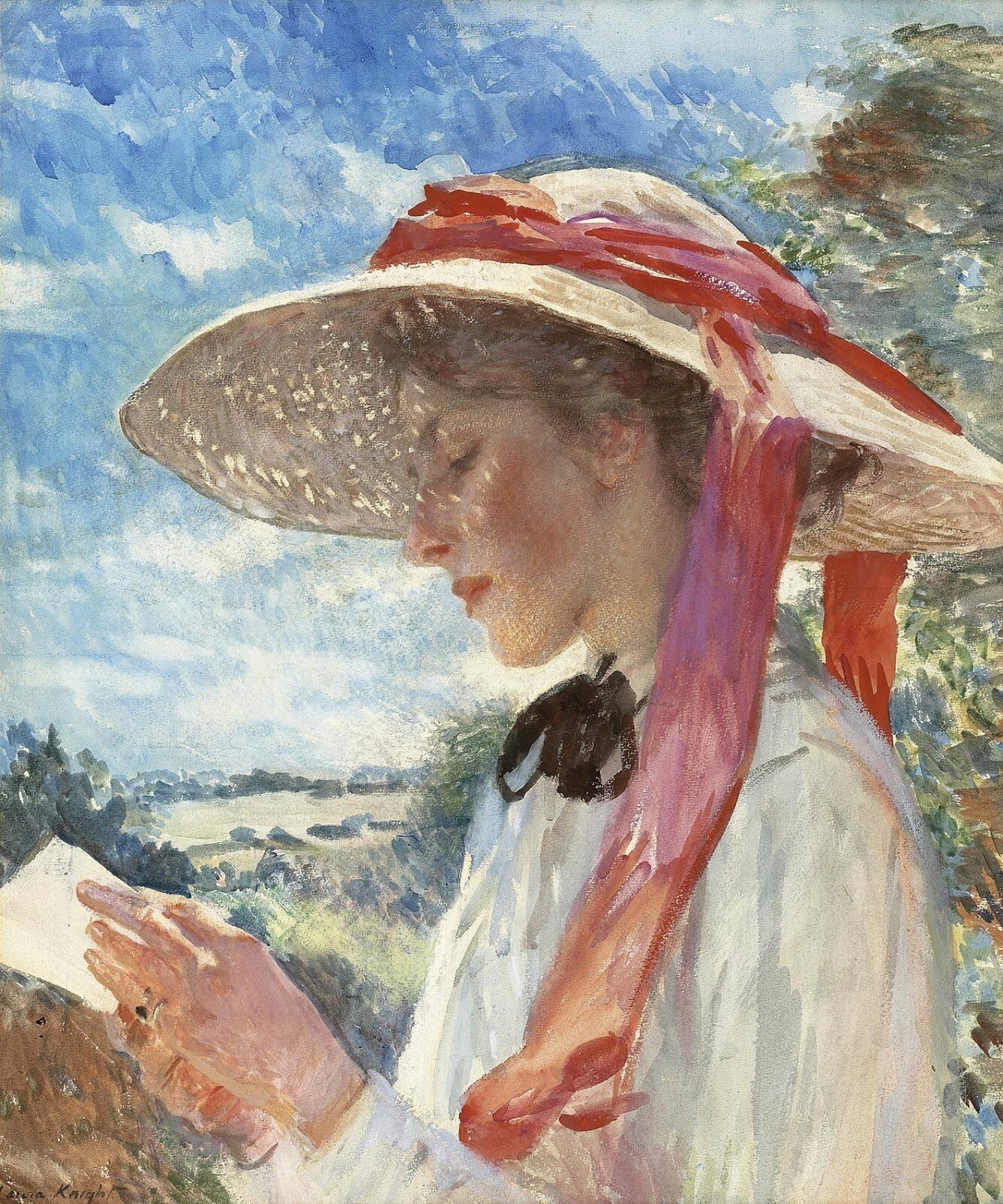

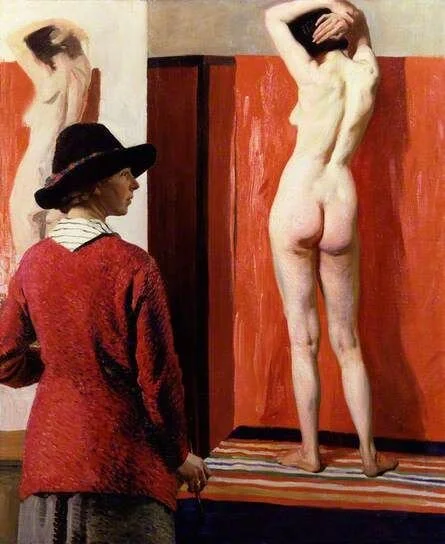

Knight's status as an artist is perhaps most salient in her Self Portrait 1913, where she depicts herself positioned alongside a nude female model. In the piece, Knight adopts two roles often occupied by men-- a professional artist and controller of gaze. However, Knight, as the subject of the work, does not succumb to the presumed male gaze of the viewer. Instead, her gaze is positioned inward to her female subject as an artistic muse.

Knight's self-portrait also diverts from social norms as female portraiture historically served to advertise women fit for marriage. However, like the fictional Jo March, Knight utilizes portraiture to advance her professional career rather than suitability for marriage.

Knight controls the depiction of herself and the female model. In addition, Knight's mastery of the female nude certifies her as an artist, once only possible for men. Similarly, Alcott's novel and Gerwig's adaptation advance the stories of four independent women from women's minds, expressing their desires beyond those restricted by gender.